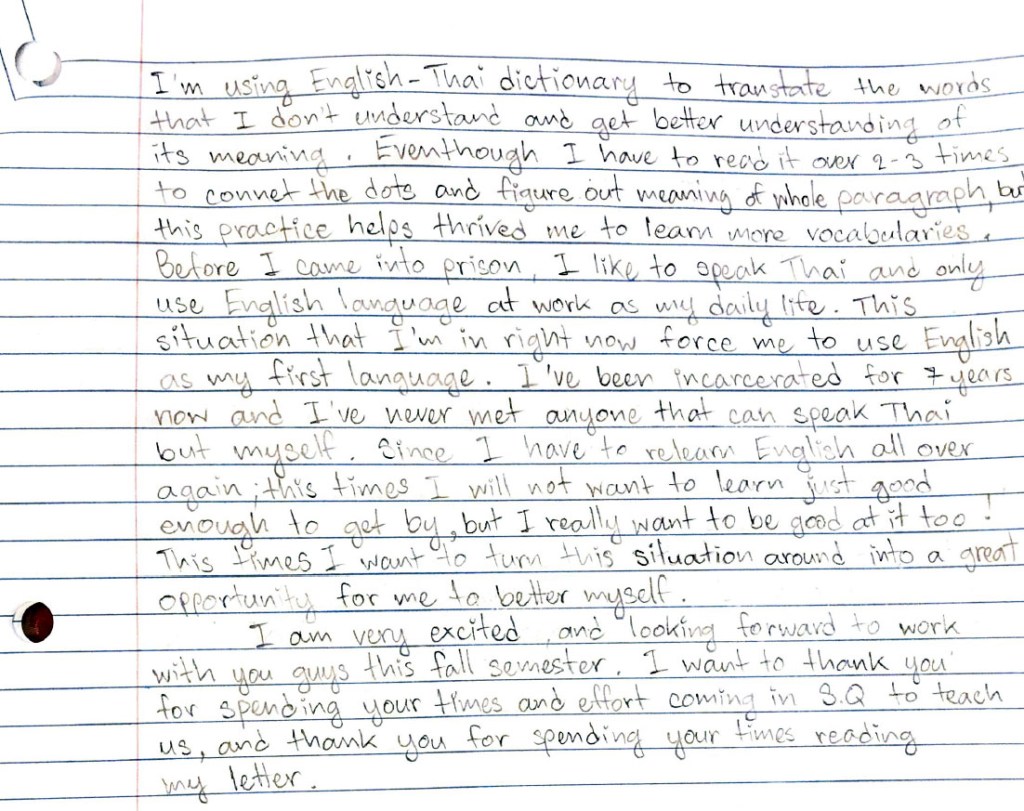

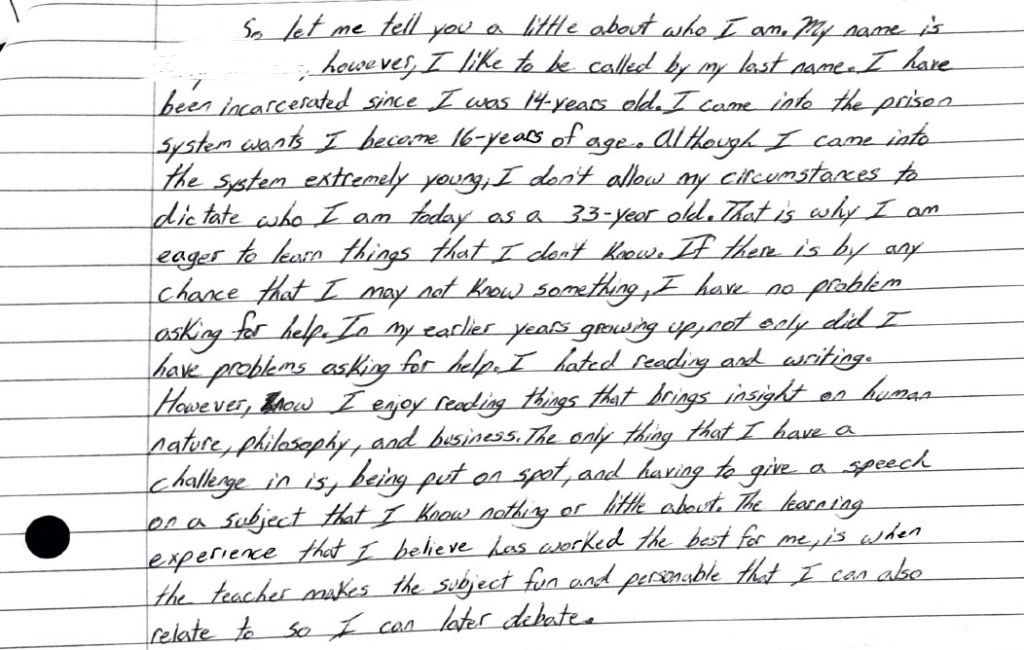

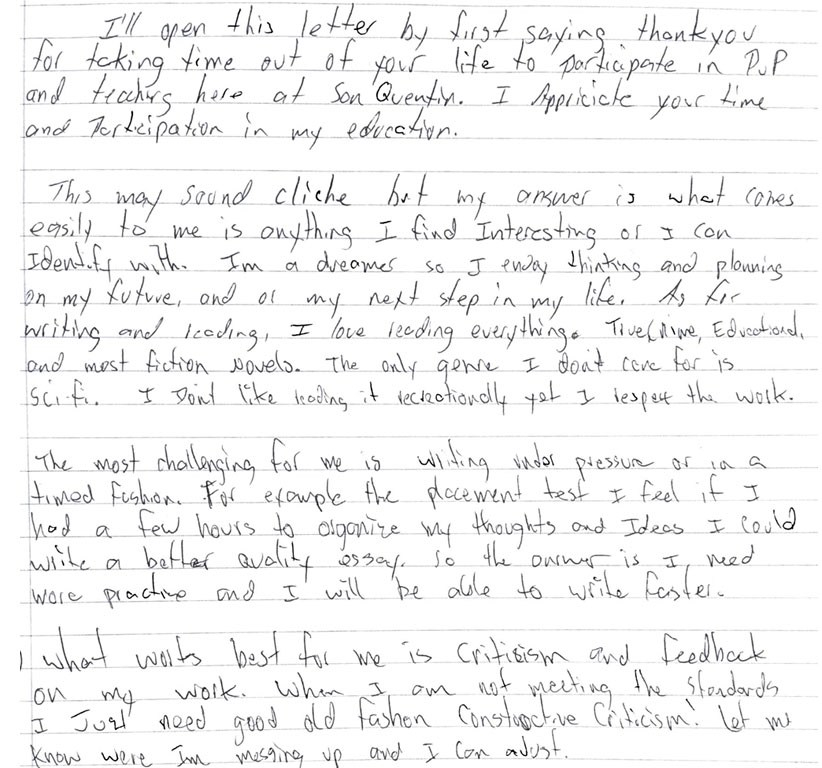

My hope, in undertaking this project, to is to amplify the voices of incarcerated students, in part because these students are not allowed to participate in every day discourses. However, in order provide context, I’d like to share an overview of my own history and educational experience as a student. If you’d like to skip this section and move to the next, click here to return to the navigation menu.

First, and most importantly, I want to emphasize that the challenges I’ve experienced in school pale in comparison to those of many, many students. This is largely due to the following:

- I grew up in a household with two white, college-educated parents, who were able to afford preschool and childcare.

- My parents were married and owned the house we lived in; my sister and I didn’t have to worry about switching schools due to evictions or rent increases.

- I attended the same school from kindergarten through eighth grade, and while I might have some valid complaints about my early education, I admit that it was consistent.

- One (or both) of my parents read to my sister and me every night, and we regularly took trips to local bookstores where our parents bought books for us.

- Growing up, my sister and I knew that we each had “college money” in some ambiguous bank account somewhere, a sort of motivational safety net.

If you don’t get it, you aren’t trying hard enough.

However, I discovered in second grade that I had what appeared to be a debilitating and detrimental math problem. Try as I might, adding the complexity of borrowing and carrying to math problems simply made no sense to me. In third grade, I discovered that multiplication tables where going to present a real problem in my life. My third grade teacher, Ms. McCahon, and her teaching aid, Ms. Hassett, both employed a “tough love” approach to struggling students–which is when I learned that if I did not understand something, it was because I wasn’t trying hard enough.

“Alexandra. You need to pay more attention. Why don’t you understand this? The rest of the class does.”

In addition to not learning math, I also learned that beginning to cry out of frustration is very, very bad. (Crying is also an involuntarily, visceral reaction I still have to this day when I don’t understand something and feel ashamed or helpless because of it. Yes, I cried in a graduate seminar because I couldn’t understand the math behind calculating reliability. At the age of 33. Fully understanding that my future beyond that specific class wouldn’t require me to ever know this.) Third grade taught me that one-on-one tutoring sessions can only lead to one place: confirmation that I was a failure as a human being.

“Alexandra. Stop crying. I know you’re just trying to convince me to let you go to recess.”

Repeat this scenario at least 50 more times before my eighth grade graduation.

(As an aside, I’ve since learned that accusing a child under the age of 10 of intentional emotional manipulation can really do a number on that child’s self-esteem, self-awareness, and ability to identify and appropriately cope with emotions. Creating a stressful learning environment for a student who is already struggling doesn’t actually help that child learn. But, that’s for another paper.)

Oh, wait. Maybe you’re not just lazy.

In any case, I floundered through school until a therapist I was seeing at the age of 15 suggested that my parents have me tested for learning differences. While coping with the never-ending struggles of academics, I also developed what I now recognize as chronic anxiety and depression (these were also generally disregarded as exaggeration or attention-seeking or a lack of resilience for most of my formative years, so I assumed I was probably just defective). But, eventually these issues were acknowledged and my parents were able to cover the costs of mental care with low-deductible, employer-provided health insurance. Still, I came dangerously close to failing out of high school during my junior year. This was partially due to several weeks of mononucleosis, partially due to my lack of motivation and failure to prioritize school over what had become frequent (over)indulgence in illicit substances. In response, my mom, the school special resource teacher, and the principal sat down with me and decided that I would be better off enrolling in a dual-enrollment program, Cañada Middle College, at the local community college rather than transferring to a continuation school.

Continuation school or college?

A stable home environment, parents who knew not only how to advocate for me but how to navigate the system has provided me with opportunities like enrolling in Cañada Middle College. Middle College allowed me to start college classes as I completed my required high school credits instead of transferring to a heavily-policed continuation school, complete remedial course packets, and maybe end up with a diploma at the end. By enrolling in Middle College, I was allowed to take courses that I found interesting, and was provided support without the shame that I had come to associate with school. To fulfill the remaining requirements needed for a high school diploma, Middle College students took high school English and US History, Government, and Economics on the college campus with teachers employed with the high school district. The teachers, who we called by their first names, Jen and Mitch, offered academically rigorous classes, challenging us without micromanaging. I made the college Dean’s List my first semester in Middle College after earning A’s in my college courses–a far cry from the sub-2.0 GPA I’d carried the semester prior.

So, is this actually a real degree?

After graduating high school, I eventually completed my general education requirements at Cañada Community College, and transferred to a bachelor’s degree completion program at the California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS) in San Francisco. The BA program at CIIS was nothing like I’d ever experienced before–the classes were pass/fail, the professors did not give tests, and the courses had names like, “Self and Society.” In other words, my explanations about the work I was doing in my BA program often prompted my parents to ask, “…so this is school actually accredited, right?”

Luckily, it was. CIIS gave me the words to describe the tensions and anxieties I had experienced throughout my childhood education. Our first assigned readings were Ira Shor’s Education is Politics: Paulo Freire’s Critical Pedagogy and chapter 1 from bell hooks’ book, Teaching to Transgress. I finally began to understand that it was okay if my brain didn’t “memorize and regurgitate” as well as my classmates’ brains did–because there was, apparently, more to school than parroting the teacher’s words. For the next three semesters, I reveled in complex texts that I rarely understood without the perspectives of my older, more worldly classmates. We talked about social constructs, hegemony, colonialism, paradigmatic research methods, and attitudes around stigma. Our cohort’s lead professor, Fernando Castrillon, was just completing his dissertation for his PsyD, and had written his thesis on the imposition of technology on culture, using critical scholars like Jacques Lacan, Michel Foucault, and DeLeuze & Guattari for framework. At least 20 of us showed up to hear him defend his thesis.

What now?

After graduating from CIIS in at the end of 2007, I spent a long time trying to just be a normal, functioning adult. I had a hard time finding a full time job with my new BA in interdisciplinary studies (although, in hindsight, 2008 was probably not a great year for very many new graduates). After being laid off from a job I absolutely detested in August 2012, I started working at the ranch where I have ridden horses since childhood, and eventually began teaching riding lessons. In 2015, I finally had enough self-confidence to imagine myself going back to school. I could maybe teach college one day, in a pinch.

With the help of a book I’d purchased on Amazon to guide me through the process of writing a personal statement and information gathered from the internet, I applied to master’s program in communication studies at San Jose State University. I didn’t know any of the faculty or students in the program. I contacted my professors (including Fernando) from nearly a decade earlier to request letters of recommendation. I transcribed a hard copy of a 12-page literature review I’d written in 2007 as a writing sample. The whole process felt very…shaky. I just about fainted when I received an email of acceptance.

Turns out, school was easier at 32.

Weirdly, going back to school was not too difficult. The time management part was (is), but the material was fascinating and I loved my professors. Understanding my own capabilities, knowing that whether or not I earned a master’s degree was my own choice, and especially (finally) believing that my value as a human was not rooted in grades allowed me to see graduate school as a purely intellectual, almost self-indulgent pursuit. Because of my life experience, I knew that grades didn’t define me and weren’t totally representative of my academic abilities (although, I did cry for a couple of minutes when I learned that I would have to re-take one of my comprehensive exams during my third semester. Old thought patterns die hard, I suppose). In any case, I graduated with a master’s degree in communication studies in May 2018, with a cumulative GPA of 3.92. I learned that, unfortunately or not, everything I’d internalized over the course of my life about value and self-worth equating to a letter grade or GPA did not weigh as heavily on hiring decisions as I’d once thought. That was okay; I’d thoroughly enjoyed spending two years digging into critical theory, pedagogy, constructivism, and studies of rhetoric. (Luckily, I had saved my readings and textbooks from CIIS.)

Back for more.

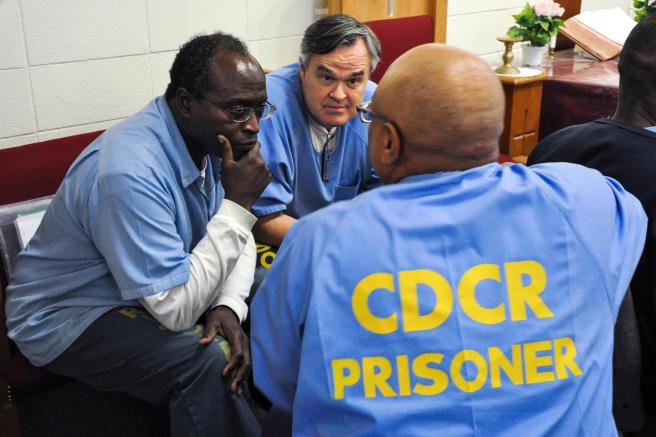

And now, here I am. Back for a second master’s degree. Learning to be a better teacher. Learning to hone the skills that will, hopefully, help students develop their own voices; especially students who may not have had the benefits of parent or teacher advocacy when they were struggling, the privileges that come with attending a small public school in an affluent community, the everyday practice of reading or of being read to as a child. The students whose voices, norms, and cultural values fall outside the margins of dominant discourses. If I, a white person from an affluent community, the daughter of two educated parents, who grew up in a safe neighborhood without exposure to gangs, guns, or drugs, could experience such trouble in school…what happens to the many students whose circumstances don’t include these elements of support? How much potential, how many brilliant minds are locked up behind walls and razor wire? I don’t claim to know, but I’m going to make sure I do everything I can to help make their voices heard.