A shift in focus

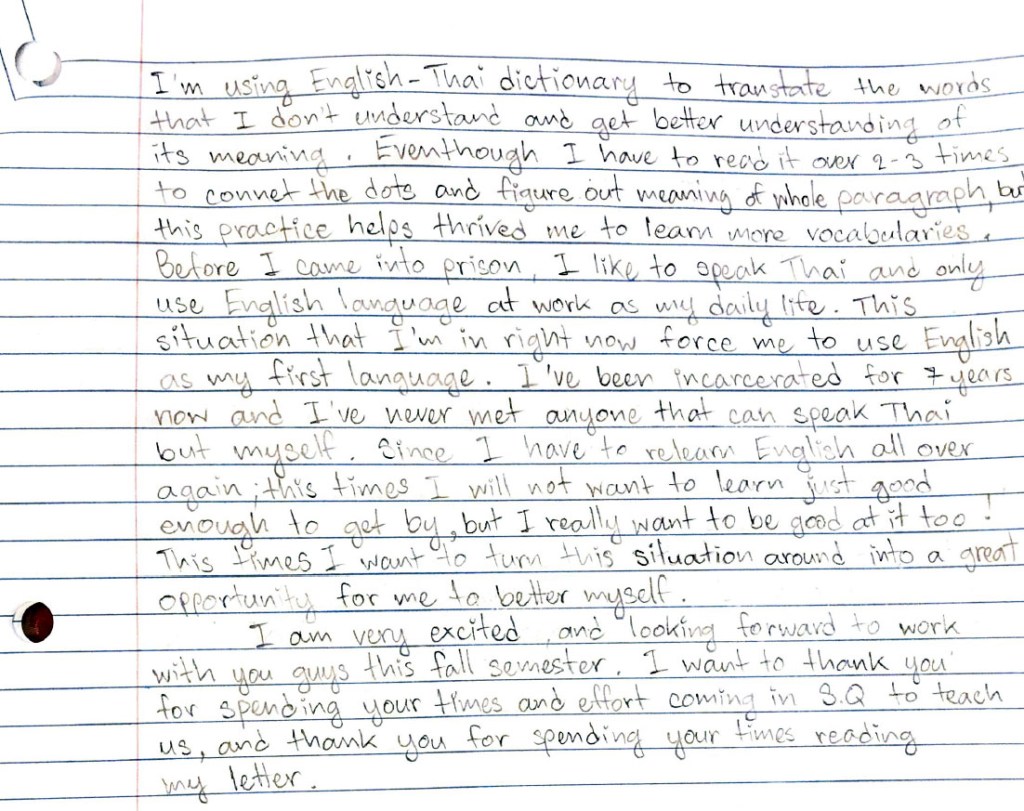

The first time I taught English 99B, over this last summer, I focused primarily on student writing. I was nervous that discussing the readings would only serve to impose my agenda, or my interpretations, on students, and that caused a great deal of concern for me. I didn’t want to tell them what meaning to make of the readings, but I didn’t know how to address teaching reading without doing just that. So, I focused heavily on writing because I felt that I was ill-equipped to offer varying perspectives on the readings and therefore did not offer students very much in terms of reading assistance. My course uses curriculum that was developed specifically for the PUP preparatory program by someone who has more teaching experience than I do, so I tend to defer to the assignments that have been paired with the readings in the past.

Click for more information about PUP’s College Prep program.

Where to start?

Teaching the English 99B course for the second time during this current semester has been a vastly different experience than the first time. Using facets of the many theoretical approaches detailed in our ENG 701 readings has provided an incredibly useful foundation on which to help students develop reading strategies.

One of my main goals in the 99B course, I realized, is to facilitate student learning in terms of transferable knowledge and prepare students not only for English 101A, but for future courses. When I read Tara Lockhart and Mary Soliday’s article, The Critical Place of Reading in Writing Transfer (2016), I decided that I needed to be a more active facilitator of developing student reading practices in order to help students develop valuable skills that will be useful as they move forward in their college careers, as well as improve confidence in their writing skills. I’m also always worried about resorting to the same methods that Adler-Kassner and Estrem warn against in Reading Practices in the Writing Classroom: seeing students as passive learners, conveying the meaning of texts rather than helping students develop ways in which to engage with texts.

Not to mention, students might even find their readings more interesting if they were shown multiple ways in which to engage with the texts.

As a relatively new teacher, I find that I often lack the experience needed to effectively scaffold my ambitious ideas, so I knew I’d need to begin with smaller exercises rather than high-stakes projects. I began with one of the sample assignments that Dr. Sugie Goen-Salter had graciously shared with our class, a guided annotation exercise, and completed it as I read the next week’s assigned reading, Sonny’s Blues by James Baldwin. In our next class, I handed out both the blank template and my own completed annotations as an example. In the past, I’ve been hesitant to offer my own work as examples of assignments, worried that I was assuming a voice of authority, but I’ve learned that sometimes, I need to prioritize guidance over worrying excessively about whether or not my interpretation is the best possible example. So, off I went.

I was encouraged when several of the students asked me for more copies of the guided annotation assignment to use in the next weeks’ readings. Because stars had somehow aligned and the now-infamous short story, Bloodchild by Octavia Butler, was assigned for the next week, I decided there was no better time to introduce the difficulty paper, another sample assignment shared by Sugie.

I should pause for a moment and mention that several students in my previous English 99B class over the summer had a hard time with this particular text. The students were offended by the reversal of gender roles and generally unhappy that a “feminist” author had been assigned in an English class, and I was unprepared in terms of framing and scaffolding. It was a blip in an otherwise smooth semester, and I was determined to do better the second time around.

Reading ‘Bloodchild’

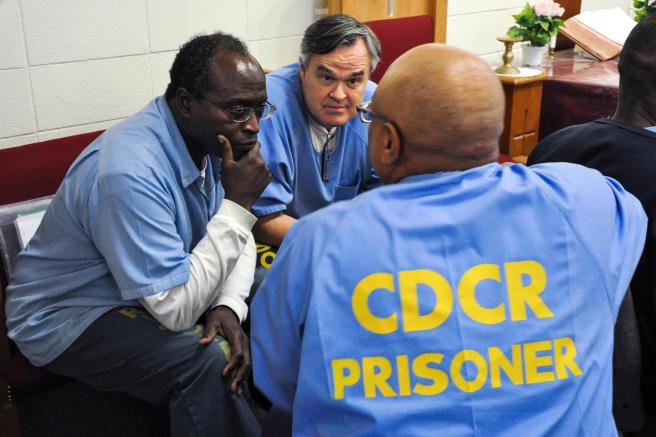

So, this semester I decided that instead of having the students read Bloodchild outside of class, we would read the story aloud in-class. Before distributing the difficulty paper and beginning to read the story, I provided students with my adaptation of my high school English teacher’s introduction to the feminist literary perspective. The purpose of this introduction was an effort to reassure students that I wasn’t trying to make them dive head-first into the feminist perspective.

Then, we read Bloodchild in its creepy, disturbing entirety out loud; each student (including one of my students from my communication studies course, who decided to sit in on the class that day when he heard we were talking about feminism), our TA, and I read a page of the story. Once we had completed the story, the students spent 10 minutes writing about the difficulties they had experienced with the text: everything from confusion in understanding the relationships between the characters to implications around gender and power dynamics.

Rather than attempting to somehow convince students that their perspectives were incorrect, or that they were correct, or that my reading was somehow more valid because I was the teacher, the difficulty paper assignment allowed us to identify and discuss, as a class, components of the text that were problematic. We used the “believing game” to consider how gender roles could have played a part in the story (meaning, taking a hypothetical stance on an issue rather than necessarily arguing one’s true viewpoint). This provided students a platform on which to engage with the text and consider a perspective that they may not have otherwise been able to recognize. It also, hopefully, provided a tool that will help them in future English courses and across the disciplines.

Willingness to engage, even if the student doesn’t necessarily agree with or even understand the author’s message, is a crucial part of participation in a community. Willingness to push through, to continue despite tension, can determine the difference between whether or not a student completes a class. Helping students explore ways in which to persist through these challenges is crucial to student success, both in the classroom and beyond.

Freire, P. (1993). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum. Original work published in 1970. Print.

Freire, P. (1993). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum. Original work published in 1970. Print.